The

underground

fungi

networks

that

help

sustain

Earth’s

ecosystems

are

in

need

of

urgent

conservation

action,

according

to

researchers

from

the

Society

for

the

Protection

of

Underground

Networks

(SPUN).

The

scientists

found

that

90

percent

of

mycorrhizal

fungi

biodiversity

hotspots

were

located

in

unprotected

ecosystems,

the

loss

of

which

could

lead

to

lower

carbon

emissions

reduction

rates,

crop

productivity

and

reduce

the

resilience

of

ecosystems

to

climate

extremes.

Mycorrhizal

fungi

“cycle

nutrients,

store

carbon,

support

plant

health,

and

make

soil.

When

we

disrupt

these

critical

ecosystem

engineers,

forest

regeneration

slows,

crops

fail

and

biodiversity

above

ground

begins

to

unravel…

450m

years

ago,

there

were

no

plants

on

Earth

and

it

was

because

of

these

mycorrhizal

fungal

networks

that

plants

colonised

the

planet

and

began

supporting

human

life,”

said

Executive

Director

of

SPUN

Dr.

Toby

Kiers,

as

The

Guardian

reported.

“If

we

have

healthy

fungal

networks,

then

we

will

have

greater

agricultural

productivity,

bigger

and

beautiful

flowers,

and

can

protect

plants

against

pathogens.”

Excited

to

get

these

data

into

the

hands

of

decision

makers.[image

or

embed]—

Society

for

the

Protection

of

Underground

Networks

(SPUN)

(@spun.earth)July

25,

2025

at

4:21

AM

Using

over

2.8

billion

fungal

sequences

from

130

countries,

the

scientists

were

able

to

create

high-resolution,

predictive

biodiversity

maps

of

the

planet’s

underground

mycorrhizal

fungal

communities.

“For

centuries,

we’ve

mapped

mountains,

forests,

and

oceans.

But

these

fungi

have

remained

in

the

dark,

despite

the

extraordinary

ways

they

sustain

life

on

land,”

Kiers

said

in

a

press

release

from

SPUN.

“This

is

the

first

time

we’re

able

to

visualize

these

biodiversity

patterns

—

and

it’s

clear

we

are

failing

to

protect

underground

ecosystems.”

The

research

was

the

first

time

a

scientific

application

of

SPUN’s

2021

world

mapping

initiative

was

done

on

a

large

scale.

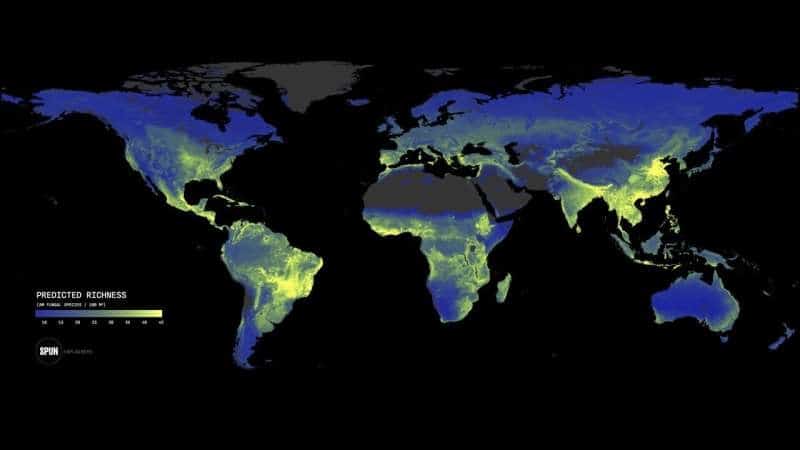

Map

from

SPUN’s

Underground

Atlas

shows

predicted

arbuscular

mycorrhizal

biodiversity

patterns

across

underground

ecosystems.

Bright

colors

indicate

higher

richness

and

endemism.

SPUN

Mycorrhizal

fungi

help

regulate

the

world’s

ecosystems

and

climate

by

forming

underground

networks

through

which

they

provide

essential

nutrients

to

plants

and

draw

more

than

13

billion

tons

of

carbon

annually

into

soils

—

roughly

a

third

of

global

fossil

fuel

emissions.

“Despite

their

key

role

as

planetary

circulatory

systems

for

carbon

and

nutrients,

mycorrhizal

fungi

have

been

overlooked

in

climate

change

strategies,

conservation

agendas,

and

restoration

efforts,”

the

press

release

said.

“This

is

problematic

because

disruption

of

networks

accelerates

climate

change

and

biodiversity

loss.”

Just

9.5

percent

of

fungal

biodiversity

hotspots

are

found

inside

existing

protected

areas.

“For

too

long,

we’ve

overlooked

mycorrhizal

fungi.

These

maps

help

alleviate

our

fungus

blindness

and

can

assist

us

as

we

rise

to

the

urgent

challenges

of

our

times,”

said

Dr.

Merlin

Sheldrake,

impact

director

at

SPUN.

SPUN

is

featured

in

@science.org

in

a

piece

written

by

@humbertobasilio.bsky.social.

Learn

where

some

of

the

most

unique

fungal

communities

exist,

such

as

West

Africa’s

Guinean

forests,

Tasmania’s

temperate

rainforests,

and

Brazil’s

Cerrado

savanna.

Read

here:

www.science.org/content/arti…

[image

or

embed]—

Society

for

the

Protection

of

Underground

Networks

(SPUN)

(@spun.earth)

July

25,

2025

at

6:33

AM

SPUN

was

launched

with

the

aim

of

mapping

fungal

communities

to

develop

resources

for

decision-makers

in

policy,

law

and

climate

and

conservation

initiatives.

“Conservation

groups,

researchers,

and

policymakers

can

use

the

platform

to

identify

biodiversity

hotspots,

prioritize

interventions,

and

inform

protected

area

designations.

The

tool

enables

decision-makers

to

search

for

underground

ecosystems

predicted

to

house

unique,

endemic

fungal

communities

and

explore

opportunities

to

establish

underground

conservation

corridors,”

SPUN

said.

The

findings

of

the

study,

“Global

hotspots

of

mycorrhizal

fungal

richness

are

poorly

protected,”

were

published

in

the

journal

Nature.

“These

maps

are

more

than

scientific

tools

—

they

can

help

guide

the

future

of

conservation,”

said

lead

author

of

the

study

Dr.

Michael

Van

Nuland,

lead

data

scientist

at

SPUN.

“Food

security,

water

cycles,

and

climate

resilience

all

depend

on

safeguarding

these

underground

ecosystems.”

Prominent

advisors

to

the

work

include

conservationist

Jane

Goodall,

authors

Paul

Hawken

and

Michael

Pollan,

and

founder

of

the

Fungi

Foundation

Giuliana

Furci.

“The

idea

is

to

ensure

underground

biodiversity

becomes

as

fundamental

to

environmental

decision-making

as

satellite

imagery,”

said

Jason

Cremerius,

SPUN’s

chief

strategy

officer.

The

maps

will

be

crucial

in

leveraging

fungi

for

the

regeneration

of

degraded

ecosystems.

“Restoration

practices

have

been

dangerously

incomplete

because

the

focus

has

historically

been

on

life

aboveground,”

said

Dr.

Alex

Wegmann,

a

lead

scientist

at

The

Nature

Conservancy.

“These

high-resolution

maps

provide

quantitative

targets

for

restoration

managers

to

establish

what

diverse

mycorrhizal

communities

could

and

should

look

like.”

The

international

network

of

96

“Underground

Explorers”

from

nearly

80

countries

and

more

than

400

scientists

are

currently

sampling

the

most

remote

and

hard-to-access

underground

ecosystems

on

Earth,

including

those

in

Bhutan,

Mongolia,

Ukraine

and

Pakistan.

While

just

0.001

percent

of

the

surface

of

our

planet

has

been

sampled,

SPUN’s

dataset

already

includes

more

than

40,000

specimens

representing

95,000

mycorrhizal

fungal

taxa.

“These

maps

reveal

what

we

stand

to

lose

if

we

fail

to

protect

the

underground,”

Kiers

said.