The

Euchloron

megaera

moth

is

a

nocturnal

pollinator

of

orchids.

Francis

DEMANGE

/

Gamma-Rapho

via

Getty

Images

Why

you

can

trust

us

Founded

in

2005

as

an

Ohio-based

environmental

newspaper,

EcoWatch

is

a

digital

platform

dedicated

to

publishing

quality,

science-based

content

on

environmental

issues,

causes,

and

solutions.

Pollinators

are

essential

for

the

reproduction

of

most

plant

species,

including

many

major

food

crops,

as

well

as

for

the

maintenance

of

healthy

ecosystems.

A

new

research

review

by

scientists

at

Lund

University

in

Sweden

has

found

that

—

in

90

percent

of

cases

studied

—

nocturnal

pollinators

like

moths

are

just

as

important

as

bees

and

other

daytime

pollinators.

“The

daily

transition

between

day

and

night,

known

as

the

diel

cycle,

is

characterised

by

significant

shifts

in

environmental

conditions

and

biological

activity,

both

of

which

can

affect

crucial

ecosystem

functions

like

pollination,”

the

authors

of

the

findings

wrote.

“Our

synthesis

revealed

an

overall

lack

of

difference

in

pollination

between

day

and

night;

many

plant

species

(90%

of

studied

spp.)

exhibit

similar

pollination

success

across

the

diel

cycle.”

For

more

than

six

decades,

scientists

have

been

trying

to

determine

whether

the

pollination

of

plants

happens

mostly

during

daylight

hours

or

at

night,

without

any

clear

conclusion

being

reached,

a

press

release

from

Lund

University

said.

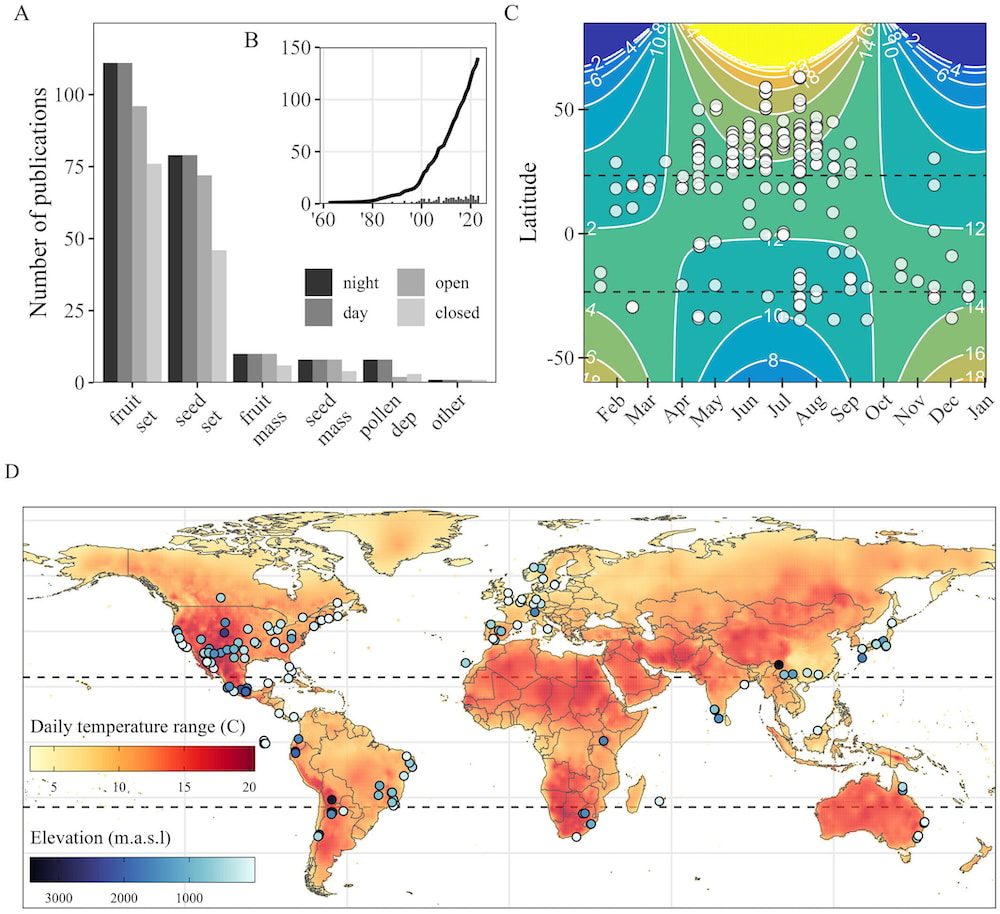

The

research

into

diel

pollination

differences

examined

different

pollination

outcomes

between

night,

day,

open,

and

closed

pollination

treatments

(A),

progressed

over

time

(B),

occurred

across

a

range

of

daylengths

(C),

temperature

conditions,

and

elevations

(D).

The

time

series

(B)

shows

the

cumulative

(line)

and

annual

(bars)

number

of

publications.

Each

study’s

daylength

(C,

hours)

was

computed

using

each

study’s

location

and

median

date.

Daily

temperature

range

and

elevation

(D)

were

extracted

based

on

study

location

(see

Methods).

Ecology

Letters (2024).

DOI:

10.1111/ele.70036

Most

people

are

aware

of

the

importance

of

bees,

butterflies

and

birds

for

plant

reproduction

and

agriculture,

but

less

attention

has

been

given

to

pollinators

who

are

active

at

night,

like

bats,

nocturnal

butterflies

and

moths.

And

these

equally

important

pollinators

don’t

just

get

less

recognition

—

they

are

also

less

protected

than

their

daytime

counterparts.

The

interest

of

Liam

Kendall

and

Charlie

Nicholson,

researchers

from

Lund

University,

in

nocturnal

pollinators

was

piqued

when

they

ran

across

studies

exploring

individual

plant

species

that

are

pollinated

in

the

daytime

versus

at

night.

They

suspected

that

previous

research

might

have

overlooked

nocturnal

pollinators.

Kendall

and

Nicholson

put

together

data

from

135

studies

around

the

world

and

found

that,

of

the

139

species

of

plants

examined,

90

percent

had

similar

reproductive

success

whether

they

were

pollinated

at

night

or

during

the

day.

“We

were

definitely

surprised

by

the

number

of

plant

species

where

it

didn’t

matter.

We

found

this

really

fascinating

because

it’s

easy

to

assume

that

a

specific

plant

needs

a

specific

pollinator.

The

analysis

actually

showed

almost

the

opposite

—

there’s

much

more

flexibility.

A

different

pollinator

than

expected

can

contribute

enough

for

a

plant

species

to

reproduce,”

Kendall

said.

The

results

of

the

first-of-its-kind

global

meta-analysis

bring

up

questions

of

human

biases

in

science.

Kendall

hypothesized

that

many

researchers

have

likely

had

a

fixed

idea

of

how

pollination

for

certain

plants

should

occur.

Kendall

also

speculated

that

most

people

being

active

during

daylight

hours

could

lead

to

them

overlooking

what

happens

while

they’re

sleeping.

“We

have

this

idea

that

all

the

magic

happens

during

the

day,

because

that’s

when

we’re

active,

and

that’s

when

we

see

bees

and

butterflies

fluttering

around

flowers,”

Kendall

said.

Kendall

believes

daytime

pollinators

being

seen

as

beautiful

is

a

factor

as

well.

“Bees

are

such

a

big

part

of

our

cultural

identity.

We

learn

that

they’re

important.

And

they’re

fluffy

and

cute

to

look

at.

While

moths

—

I

mean,

they

have

their

prettier

cousins,

the

butterflies,

which

we

love,

but

moths

are

gray

and

dusty,

and

they

eat

your

clothes.

How

could

they

possibly

do

anything

positive?”

Kendall

added.

Given

human

activity’s

pressure

on

biodiversity,

the

researchers

said

their

study

calls

attention

to

the

importance

of

considering

daytime

and

nocturnal

pollinators

in

conservation

and

agriculture.

[embedded content]

For

example,

Kendall

said

the

life

cycle

of

a

moth

is

entirely

different

from

that

of

a

bee,

so

their

ecological

needs

are

different.

“The

analysis

shows

that

we

need

to

change

the

way

we

think

about

how

environments

can

support

pollinators

and

biodiversity,”

Kendall

said.

And

if

pollination

at

night

is

really

important,

it

becomes

critical

to

avoid

light

pollution

—

excessive

or

badly

placed

lighting

that

disturbs

the

natural

environment.

“Actions

are

often

taken

to

protect

daytime

pollinators,

such

as

spraying

pesticides

at

night.

There’s

an

oversight

there

—

sure,

you’re

protecting

the

daytime

insects,

but

you’re

also,

theoretically,

harming

the

nocturnal

pollinators.

This

means

we

could

be

doing

much

more,

but

we

haven’t

thought

enough

about

it

so

far,

and

more

research

is

needed,”

Kendall

said.

The

study,

“Pollination

Across

the

Diel

Cycle:

A

Global

Meta-Analysis,”

was

published

in

the

journal

Ecology

Letters.

[embedded content]

Subscribe

to

get

exclusive

updates

in

our

daily

newsletter!

By

signing

up,

you

agree

to

the

Terms

of

Use and Privacy

Policy,

and

to

receive

electronic

communications

from

EcoWatch

Media

Group,

which

may

include

marketing

promotions,

advertisements

and

sponsored

content.